1864 CIVIL WAR Diary SOLDIER Battles NEGRO Fugitive SLAVE SPEAKER Plainfield VT

1864 CIVIL WAR DIARY, FREED SLAVE SPEAKER. FANTASTIC 1864 CIVIL WAR DIARY KEPT BY A HOPEFUL GIRLFRIEND IN VERMONT.

WHILE HER LOVE FOUGHT IN THE WAR. WAS SUBSEQUENTLY WOUNDED AT THE BATTLE OF SPOTSYLVANIA. AND TRANSFERRED TO THE INVALID CORPS. THIS 1864 DIARY WAS KEPT BY HENRIETTA SEVERANCE, WHO LATER WENT ON TO MARRY AMOS C. BRADFORD, BOTH OF WASHINGTON COUNTY, VERMONT (PLAINFIELD/MONTPELIER).

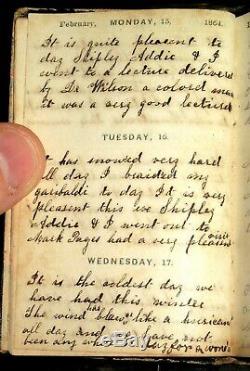

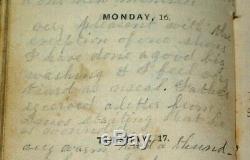

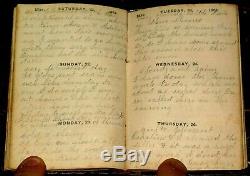

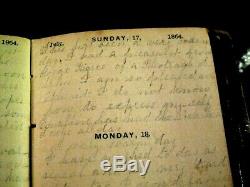

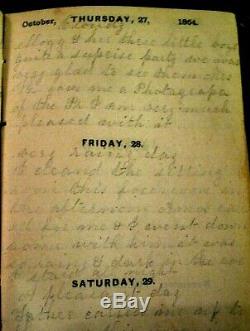

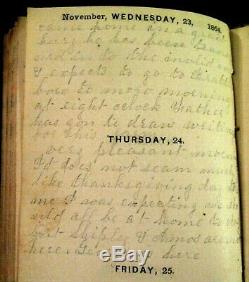

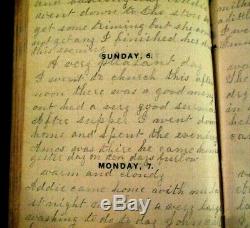

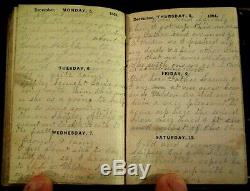

WHILE HETTIE LIVED HOME (SHE WAS ONLY 23 AT THE TIME OF THE DIARY), SHE TALKS OF DAY TO DAY LIFE HEARING ABOUT GREAT BATTLES AND FIELD NEWS, SHE WENT TO HEAR A'COLORED MAN' SPEAK A DR. WILSON, WHO WAS THOMAS WILSON, A FREED SLAVE TURNED ABOLITIONIST, PERHAPS BEST KNOWN AS THE FIRST HUSBAND OF HARRIET WILSON, NOTABLE EX SLAVE AUTHOR AND NOVELIST, AND ENJOYS TIME WITH AMOS WHILE ON SMALL FURLOWS. SHE GETS A PHOTO OF HER BOYFRIEND AT ONE POINT, GETS A PHOTO DONE OF HERSELF, AND TRAVELS WITH HER FRIEND IN TOWN (PLAINFIELD, VT), AND EVEN GOES FISHING AT ONE POINT. HER FAMILY EVENTUALLY MOVED TO WALDEN, VT AT THE END OF THE DIARY.

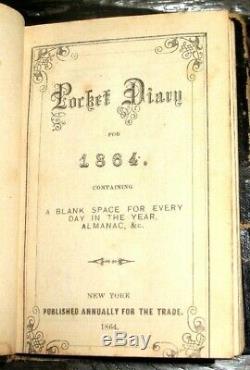

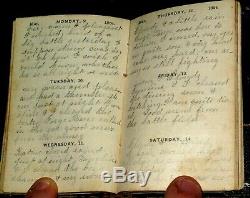

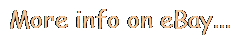

A TOUCHING ENDING TO THE DIARY IS ANOTHER HAND (PRESUMABLY AMOS'), WHERE IT IS WRITTEN'REMEMBER ME, WHEN DISTANT LANDS DIVIDE US', LIKELY WRITTEN WHILE HE WAS AWAY AT WAR FOR HER TO SEE. IT IS A DAILY DIARY, BOUND IN BLACK LEATHER IN A SLIP CATCH WALLET STYLE FORMAT, SOME POCKET WEAR BUT ALL ONE PIECE. ALL PAGES BOUND, MOSTLY WRITTEN IN PENCIL (LIGHT AT TIMES), BUT SOME PEN ENTRIES AS WELL. NEARLY EVERY DAY IS USED WITH THE EXCEPTION OF PERHAPS 5-7 PAGES.

IT MEASURES 4" X 2.5". From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Wilson (March 15, 1825 June 28, 1900) was an African-American. She was the first African American of any gender to publish a novel on the North American continent. Or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black was published anonymously in 1859 in Boston. And was not widely known. The novel was discovered in 1982 by the scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Who documented it as the first African-American novel published in the United States. Born a free person of color (free Negro) in New Hampshire.Wilson was orphaned when young and bound until the age of 18 as an indentured servant. She struggled to make a living after that, marrying twice; her only son George died at the age of seven in the poor house, where she had placed him while trying to survive as a widow. Wilson later was associated with the Spiritualist. Church, was paid on the public lecture circuit.

For her lectures about her life, and worked as a housekeeper in a boarding house. "Hattie" Adams in Milford, New Hampshire. Daughter of Margaret Ann (or Adams) Smith, a washerwoman of Irish ancestry, and Joshua Green, an African-American "hooper of barrels" of mixed African and Indian ancestry.After her father died when Hattie was young, her mother abandoned Hattie at the farm of Nehemiah Hayward Jr. A well-to-do Milford farmer connected to the Hutchinson Family Singers.

As an orphan, Adams was bound by the courts as an indentured servant. To the Hayward family, a customary way for society at the time to arrange support and education for orphans. Gabrielle Foreman and Reginald H. Pitts believe that the Hayward family were the basis of the "Bellmont" family depicted in Our Nig.This was the family who held the young "Frado" in indentured servitude, abusing her physically and mentally from the age of six to eighteen. Foreman and Pitts' material was incorporated in supporting sections of the 2004 edition of Our Nig. After the end of her indenture at the age of eighteen, Hattie Adams (as she was then known), worked as a house servant and a seamstress. In households in southern New Hampshire.. Adams married Thomas Wilson in Milford on October 6, 1851.

An escaped slave, Wilson had been traveling around New England giving lectures based on his life. Although he continued to lecture periodically in churches and town squares, he told Hattie that he had never been a slave and that he had created the story to gain support from abolitionists. Wilson abandoned Harriet soon after they married. Pregnant and ill, Harriet Wilson was sent to the Hillsborough County, New Hampshire.

Where her only son, George Mason Wilson, was born. His probable birth date was June 15, 1852.

Soon after George's birth, Wilson reappeared and took the two away from the Poor Farm. After that, Wilson moved to Boston, hoping for more work opportunities. On September 29, 1870, Wilson married again, to John Gallatin Robinson in Boston. He was a native of Canada born in Sherbrooke, Quebec. Robinson was of English and German ancestry; he was nearly 18 years younger than Wilson.

After that date, city directories list Wilson and Robinson in separate lodgings in Boston's South End. No record has been found of a divorce, but divorces were infrequent at the time.

While living in Boston, Wilson wrote Our Nig. On August 14, 1859, she copyrighted it, and deposited a copy of the novel in the Office of the Clerk of the U. On September 5, 1859, the novel was published anonymously by George C. Rand and Avery, a publishing firm in New York. In 1863, Harriet Wilson appeared on the "Report of the Overseers of the Poor" for the town of Milford, New Hampshire. After 1863, she disappeared from records until 1867, when she was listed in the Boston Spiritualist. As living in East Cambridge, Massachusetts. She subsequently moved across the Charles River. To the city of Boston, where she became known in Spiritualist circles as the colored medium. From 1867 to 1897, Mrs.Wilson was listed in the Banner of Light as a trance reader and lecturer. She was active in the local Spiritualist community, and she would give "lectures, " either while entranced, or speaking normally, wherever she was wanted.

She spoke at camp meetings, in theaters, and in private homes throughout New England; she shared the podium with speakers such as Victoria Woodhull. In 1870 Wilson traveled as far as Chicago as a delegate to the American Association of Spiritualists convention. Wilson delivered lectures on labor reform, and children's education. Although the texts of her talks have not survived, newspaper reports imply that she often spoke about her life experiences, providing sometimes trenchant and often humorous commentary.

Closer to home, Wilson was active in the organization and maintenance of Children's Progressive Lyceums, the Spiritualist church equivalent to Sunday Schools. She organized Christmas celebrations; she participated in skits and playlets; and at meetings she sometime sang as part of a quartet. She was also known for her floral centerpieces, and the candies she would make for the children were long remembered. Wilson worked as a Spiritualist nurse and healer ("clairvoyant physician").

In addition, for nearly 20 years from 1879 to 1897, she was the housekeeper of a boardinghouse in a two-story dwelling at 15 Village Street near the present corner of Dover [now East Berkeley Street] and Tremont Streets in the South End. She rented out rooms, collected rents and provided basic maintenance. In Wilson's active and fruitful life after Our Nig, there is no evidence that she wrote anything else for publication. On June 28, 1900, Hattie E. Wilson died in the Quincy Hospital in Quincy, Massachusetts. She was buried in the Cobb family plot in that town's Mount Wollaston Cemetery.Her plot number is listed as 1337, old section. At Wilson's death, her estranged husband Robinson, describing himself as a "capitalist", was living in the town of Pembroke, Massachusetts. With a 24-year-old woman named Izah Nellie Moore. Two years later they married.

The scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Rediscovered Our Nig in 1982 and documented it as the first novel by an African American to be published in the United States. His discovery and the novel gained national attention. Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. And Mitch Kachun, a history professor at Western Michigan University. Brought to light Julia C. Or The Slave Bride (1865), first published in serial form in the Christian Recorder, the newspaper of the AME Church. Publishing it in book form in 2006, they maintained that The Curse of Caste should be considered the first "truly imagined" novel by an African American to be published in the U. They argued that Our Nig was more autobiography than fiction. Gates responded that numerous other novels and other works of fiction of the period were in some part based on real-life events and were in that sense autobiographical, but they were still considered novels. The first known novel by an African American is William Wells Brown. S Clotel; or, The President's Daughter. (1853), published in the United Kingdom, where he was living at the time. Argued that the unfinished state of The Curse of Caste (Collins died before completing it) and its poor literary quality should disqualify it as the first building block of African-American literature. He contended the works by Wilson and Brown were more fully realized. Eric Gardner thought that Our Nig did not receive critical acclaim from abolitionists when first published because it did not conform to the contemporary genre of slave narratives. He thinks the abolitionists may have refrained from promoting Our Nig because the novel recounts "slavery's shadow" in the North, where free blacks suffered as indentured servants. It fails to offer the promise of freedom, and it features a protagonist who is assertive toward a white woman. In her article "Dwelling in the House of Oppression: The Spatial, Racial, and Textual Dynamics of Harriet Wilson's Our Nig, " Lois Leveen argues that, although the novel is about a free black in the north, the "free black" is still oppressed. The "white house" of the novel represents, as Leveen puts it: The model home for American society is built according to the spatial imperatives of slavery. " Frado is a "free black, but she is treated as a lower-class person and is often abused as a slave would be. Leveen argues that Wilson was expressing her view that even the "free blacks" were not really free in a racist society.Since Henry Louis Gates, Jr's work in 1982, Harriet Wilson has been recognized as the first African American to publish a novel in the United States. The Harriet Wilson Project made a statue(2006). It can be found in the town's Bicentennial Park, in order to honor her.

"Hattie" Adams Wilson was born in Milford, New Hampshire, the daughter of Joshua Green, a Black "hooper of barrels", and Margaret Ann (or Adams) Smith, a washerwoman of Irish ancestry. Her father died when she was very young, and her mother abandoned her at the farm of Nehemiah Hayward Jr. As an orphan, Adams was made an indentured servant to the Hayward family, a customary way for society to arrange support at the time. After the end of her indenture, Hattie Adams (as she was then known), worked as a house servant and a seamstress in households in southern New Hampshire and in central and western Massachusetts.

She married Thomas Wilson in Milford on October 6, 1851. Thomas Wilson had been traveling around New England giving lectures based on his life as an escaped slave, when he met Hattie Adams.

Although he continued to periodically lecture in churches and town squares, he soon confided to her that he was never in bondage ("he had never seen the South") and that his illiterate harangues were humbugs for hungry abolitionists. Pregnant and ill, Harriet Wilson was sent to the Hillsborough County, New Hampshire Poor Farm in Goffstown, New Hampshire, where her only son, George Mason Wilson, was born in 1852. Soon after George's birth, Thomas Wilson reappeared in her life and took her and her son away from the Poor Farm. During this time while working as a dressmaker in Boston, Wilson wrote Our Nig. Which was published on September 5 1859. This was the first known American publication by any Black person. Her son died of fever on February 15, 1860, six months after the book's publication. Closer to home, Wilson was active in the organization and maintenance of Children's Progressive Lyceums, the Spiritualist church equivalent to Sunday Schools; she organized Christmas celebrations; she participated in skits and playlets; at meetings she sometime sang as part of a quartet; she was also known for her floral centerpieces and the candies and confectioneries she would make for the children. When she was not pursuing Spiritualistic activities, Hattie Wilson was employed as a nurse and healer ("clairvoyant physician"). For nearly 20 years from 1879 to 1897, she was the housekeeper of a boardinghouse in a two-story dwelling at 15 Village Street near the present corner of Dover [now East Berkeley Street] and Tremont Streets in the South End. Despite Wilson's active and fruitful life after "Our Nig", there is no evidence that she ever wrote anything else for publication. 1860 United States Federal Census. Enlisted in Company F, Vermont 2nd Infantry Regiment on 22 Sep 1862. Mustered out on 01 Jan 1865. Transferred to on 01 Jan 1865. Mustered out on 07 Jul 1865. The item "1864 CIVIL WAR Diary SOLDIER Battles NEGRO Fugitive SLAVE SPEAKER Plainfield VT" is in sale since Thursday, February 27, 2020. This item is in the category "Books\Antiquarian & Collectible". The seller is "mantosilver" and is located in Spencerport, New York.This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Printing Year: 1853

- Year Printed: 1853

- Country/Region of Manufacture: United States

- Topic: Medicine

- Binding: Softcover, Wraps

- Region: North America

- Origin: American

- Subject: Science & Medicine

- Language: English

- Special Attributes: 1st Edition