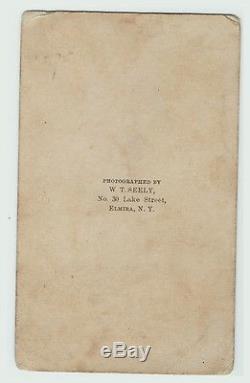

CDV Photo Union Civil War Soldier Armed Double Pistols & Knife Elmira NY 1860s

Officer with 2 Pistols and Knife. For offer, a rare CDV (carte de visite - visiting card)! Fresh from a prominent estate in Upstate NY. Never offered on the market until now. Vintage, Old, Original, Antique, NOT a Reproduction - Guaranteed!! Soldier in uniform with 2 pistols and knife. Photographer imprint on back of W. Wear to edges and corners, photo a bit faded. If you collect 19th century Americana history, American military photography, etc. This is a treasure you will not see again!

Add this to your image or paper / ephemera collection. Perhaps genealogy research importance too.

Elmira Prison was a prisoner-of-war camp constructed by the Union Army in Elmira, New York, during the American Civil War to house captive Confederate soldiers. The site was selected partially due to its proximity to the Erie Railway and the Northern Central Railway, which criss-crossed in the midst of the city, making it a prime location for a Union Army training and muster point early in the Civil War.

Most of the 30-acre (120,000 m2) Union installation, known as Camp Rathbun, fell into disuse as the war progressed, but the camp's "Barracks #3" were converted into a military prison in the summer of 1864. The prison camp, in use from July 6, 1864, until the autumn of 1865, was dubbed "Hellmira" by its inmates.Towner's history of 1892 and maps from the period indicate the camp occupied an area running about 1,000 feet (300 m) west and approximately the same distance south of a location a couple of hundred feet west of Hoffman Street and about 35 feet south of Water Street, bordered on the south by Foster's Pond, on the north bank of the Chemung River. [1][2]:265 During the 15 months the site was used as a prisoner of war camp more than 12,100 Confederate soldiers were incarcerated there; of these, nearly 25% (2,963) died from a combination of malnutrition, continued exposure to harsh winter weather, and disease from the poor sanitary conditions on Foster's Pond combined with a lack of medical care. The camp's dead were prepared for burial and laid to rest by the sexton, an ex-slave named John W.

Jones, at what is now Woodlawn National Cemetery. At the end of the war, each prisoner was required to take a loyalty oath and given a train ticket home. The last prisoner left the camp on September 27, 1865.

The camp was then closed, demolished and converted to farm land. [3][1] Woodlawn Cemetery, about 2 miles (3.2 km) north of the original prison camp site (bounded by West Hill, Bancroft, Davis, and Mary streets), was designated a National Cemetery in 1877. The prison camp site is a residential area today, and few of the city's residents are aware that the prison camp ever existed. [citation needed] However, there is a memorial at the site today.

Prison conditions Like many prison camps built hastily in the Civil War to deal with the demands created by the capture of enemy soldiers, Elmira suffered from poor health conditions and poor planning early on. The Camp was originally designed as a training barracks. Camp Rathbun, as originally designed, could support up to two thousand soldiers. [4] As the years passed and Camp Rathbun was used less and less as a training facility, plans to turn it into a prison camp were made. On May 2, 1864, Lieutenant Colonel Seth Eastman, the officer in charge of Camp Rathbun at the time, reported to Brigadier General Lorenzo Thomas that twenty barracks had been constructed and that this, in addition to repairs on old barracks, allowed Elmira to support up to 6,000 troops.

[5] On May 19, 1864, Eastman was informed via letter from Commissary General William Hoffman that he was to set apart the barracks on the Chemung River at Elmira as a depot for prisoners of war. He was also informed that the prison might be needed within ten days and that it might have to welcome 8,000 or up to 10,000 prisoners. According to Eastman's calculations, the camp could only hold half that properly. While the barracks were well kept, they could only house four thousand men, and perhaps another thousand could be kept in tents. In addition to that, Eastman reported that the kitchens could only feed five thousand a day and the mess room could only seat fifteen hundred men at once. To top all of this off, there were no hospital facilities in the camp; the soldiers instead relied on facilities in the town. [6] Still, Eastman was told to be prepared to receive prisoners, and from the beginning it would seem that the camp was destined to be overcrowded. This led to many charges that the prison camp was designed from the beginning to be not a prison, but a death camp.[7] The first Commandant of the Camp was Major Henry V. Colt of the 104th New York Volunteers. Colt was given charge over the prisoners because of an inability to serve in the field, a characteristic that many in his position in similar prison camps shared with him.

A man of relatively even temperament, Colt was able to achieve what few officers in the war were able to in that he was liked by both Union and Confederate soldiers. [8] He received his first prisoners on July 6, 1864, when 400 prisoners arrived at the camp. Though Colt was a fair man, and liked well enough by most of his prisoners, he was a man who took his duty seriously as commandant.The best evidence for this can be viewed in the case of Washington B. Traweek was a Confederate soldier who made an escape attempt from the prison along with a few other soldiers, all of them members of the Jefferson Davis Artillery Company. The escape plan involved digging a tunnel from a neighboring tent underneath the fence and into town.

Later, when a series of hospitals was to be built for the camp, the prisoners involved in Traweek's plot decided to transfer their tunnel to go underneath the hospital, and started work on a new tunnel. Others had a similar idea, and this resulted in the tunnels being discovered. The next day, Traweek was called before Major Colt.

Colt inquired as to where Traweek's tunnel was, and who had been tunneling with him. When Traweek refused to tell, Colt ordered him into a sweatbox and presided over his questioning, willing to go to extreme measures to find and persecute the tunnelers. Traweek held fast however, and Colt was forced to release him. Traweek and his companions eventually escaped. [9] Five days after the camp opened, Surgeon Charles T.

Alexander was ordered to inspect the Camp at Colonel Hoffman's request. Alexander found two major problems with the camp that he detailed in his report. The first was that of the camp's sanitary conditions.

The sinks near Foster's Pond contained stagnant water, and he feared if they were not cleaned, they might become offensive and a source of disease. He recommended the construction of new sinks. Hoffman did not heed these warnings. The other problem that Alexander identified was that of the hospitals. While the camp now had a hospital, in the form of a tent, it did not have an assigned surgeon and instead relied on the services of William C. Alexander also thought the notion of using a tent as a hospital within the prison was inappropriate, and therefore should be rectified. Hoffman allowed for three pavilion wards to be planned at Alexander's suggestion. [10] While Hoffman was open to suggestions on how to improve his prisons, he was notoriously cheap, and he was also a major proponent of retaliation should the war take a sour turn, and reduced rations to the prisoners. As a result, many prisoners in the Elmira Camp were malnourished, a state of being that harmed many of them, especially during the extreme heat of summer and the extreme cold of winter. [11] Another major problem that points to Hoffman's policy of retaliation was the construction of winter housing for the prisoners.During most of their stay, a significant portion of the prisoners in Elmira lived in tents, as there was only room for 6,000 prisoners in the barracks, while there were 10,000 prisoners. And while there was a large work force at the camp, due to the prisoner population, work on winter housing did not start until October when the cold New York nights had started to pervade the camp. The late start resulted in the deaths of hundreds of prisoners as the construction continued into the winter months.

In addition to the poor conditions of the weather, winter construction was also delayed by a lack of lumber. In November, it was also reported that the existing barracks were experiencing trouble as well, with roofs falling into disrepair and being unfit to stand the winter weather. Even in late November and early December, there were reports of over 2,000 Confederates sleeping in tents, and a Christmas inspection said that 900 were still in tents. [12] It was not until October 27, 1864 that work finally began on the draining system that Charles T. By then, the cold weather of November and December kept this project from being completed in a timely manner, and it was not completed until January 1st of the following year.In the meantime, hundreds of Confederate prisoners were subjected to stagnant and unclean water, and many became ill simply because of a lack of clean drinking water. [13] It was during this winter that the tangible signs of Hoffman's reduced rationing began to take their toll on the prisoners, as prisoners were reduced to eating rats in place of the food they would normally get. Indeed, rats became a currency in the trade system of the prisoners for other supplies.

[14] The propaganda of the Union went to great pains to make sure that the details of Hoffman's retaliations were covered up. The New York Herald denied any mistreatment of prisoners in Elmira, calling the reports a pure fabrication. " To the Herald, all rations at Elmira were sufficient and, though it admitted the unusually high incidence of illness in the camp, the newspaper said that the sickness was "beyond the control of the authorities... There is no lack of medical attendance or supplies.

Indeed, this propaganda was so powerful that the belief that the Elmira prison camp was a humane alternative to Andersonville still prevailed in some circles of thought. In a meeting in 1892, John T.Davidson, a captain of the guard detail at Camp Chemung, blamed the high mortality rate on the changing weather, water, and manner of living. He also conceded that the horrors of prison-camp life were numerous, and a condition that all men should hope to avoid. But, he said, none of these things can apply, with a shadow of truth, to the prison camp at Elmira. [15] However, by the end of the Civil War it could not be disputed that Elmira had taken a considerable toll on the prisoners who came through its doors. They dubbed the camp "Hellmira, " and the mortality rate of about 25 percent was near that of Andersonville (about 29 percent).

[citation needed] In popular culture Miserable conditions for the prisoners in the camp are depicted in the 1982 miniseries The Blue and the Gray. [16] Vincent was captured and brought to Elmira Prison in With Lee in Virginia. The American Civil War, widely known in the United States as simply the Civil War as well as other sectional names, was a civil war fought from 1861 to 1865 to determine the survival of the Union or independence for the Confederacy. Among the 34 states as of January 1861, seven Southern slave states individually declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America, known as the "Confederacy" or the "South".

They grew to include eleven states, and although they claimed thirteen states and additional western territories, the Confederacy was never diplomatically recognized by a foreign country. The states that remained loyal and did not declare secession were known as the "Union" or the "North". The war had its origin in the fractious issue of slavery, especially the extension of slavery into the western territories. [N 1] After four years of combat that left over 600,000 Union and Confederate soldiers dead and destroyed much of the South's infrastructure, the Confederacy collapsed and slavery was abolished.Then began the Reconstruction and the processes of restoring national unity and guaranteeing civil rights to the freed slaves. In the 1860 presidential election, Republicans, led by Abraham Lincoln, opposed the expansion of slavery into US territories. The Republican Party, dominant in the North, secured a majority of the electoral votes, and Lincoln was elected president, but before his inauguration on March 4, 1861, seven slave states with cotton-based economies formed the Confederacy.

The first six to secede had the highest proportions of slaves in their populations, a total of 48.8% for the six. [5] Outgoing Democratic President James Buchanan and the incoming Republicans rejected secession as illegal. Lincoln's inaugural address declared his administration would not initiate civil war. Eight remaining slave states continued to reject calls for secession. Confederate forces seized numerous federal forts within territory claimed by the Confederacy. A peace conference failed to find a compromise, and both sides prepared for war. The Confederates assumed that European countries were so dependent on "King Cotton" that they would intervene; none did and none recognized the new Confederate States of America. Hostilities began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces fired upon Fort Sumter, a key fort held by Union troops in South Carolina. Lincoln called for every state to provide troops to retake the fort; consequently, four more slave states joined the Confederacy, bringing their total to eleven.Lincoln soon controlled the border states, after arresting state legislators and suspending habeas corpus, [6] ignoring the ruling of the Supreme Court's Chief Justice that such suspension was unconstitutional, and established a naval blockade that crippled the southern economy. The Eastern Theater was inconclusive in 186162. The autumn 1862 Confederate campaign into Maryland (a Union state) ended with Confederate retreat at the Battle of Antietam, dissuading British intervention. [7] To the west, by summer 1862 the Union destroyed the Confederate river navy, then much of their western armies, and the Union siege of Vicksburg split the Confederacy in two at the Mississippi River. Lee's Confederate incursion north ended at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which made ending slavery a war goal. [8] Western successes led to Ulysses S.Grant's command of all Union armies in 1864. In the Western Theater, William T. Sherman drove east to capture Atlanta and marched to the sea, destroying Confederate infrastructure along the way. The Union marshaled the resources and manpower to attack the Confederacy from all directions, leading to the protracted Siege of Petersburg.

The besieged Confederate army eventually abandoned Richmond, seeking to regroup at Appomattox Court House, though there they found themselves surrounded by union forces. This led to Lee's surrender to Grant on April 9, 1865. All Confederate generals surrendered by that summer. The American Civil War was one of the earliest true industrial wars.

Railroads, the telegraph, steamships, and mass-produced weapons were employed extensively. The mobilization of civilian factories, mines, shipyards, banks, transportation and food supplies all foreshadowed World War I. It remains the deadliest war in American history, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 750,000 soldiers and an undetermined number of civilian casualties. [N 2] One estimate of the death toll is that ten percent of all Northern males 2045 years old, and 30 percent of all Southern white males aged 1840 died.

[10] From 1861 to 1865 about 620,000 soldiers lost their lives. Andrew Hull Foote (September 12, 1806 June 26, 1863) was an American naval officer who was noted for his service in the American Civil War and also for his contributions to several naval reforms in the years prior to the war. When the war came, he was appointed to command of the Western Gunboat Flotilla, predecessor of the Mississippi River Squadron. In that position, he led the gunboats in the Battle of Fort Henry. For his services with the Western Gunboat Flotilla, Foote was among the first naval officers to be promoted to the then-new rank of rear admiral. Early life Foote was born at New Haven, Connecticut, the son of Senator Samuel A. Foot (or Foote) and Eudocia Hull. [2] As a child Foote was not known as a good student, but showed a keen interest in one day going to sea.[3] His father compromised and had him entered at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. [4] Six months later in 1822, he left West Point and accepted an appointment as a midshipman in the United States Navy. [4] Antebellum naval service Between 1822 and 1843, Foote saw service in the Caribbean, Pacific, and Mediterranean, African Coast and at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. He first began as a midshipman on the USS Grampus. In 1830, he was commissioned a lieutenant, and was stationed in the Mediterranean.

[3] In 1837, Foote circumnavigated the globe in the USS John Adams. After serving on sea, Foote was put in charge of the Philadelphia Naval Asylum. After serving on land he went back to sea, and organized a Temperance Society aboard the USS Cumberland.

[3] This group developed into a movement that resulted in ending the policy of supplying grog to U. He was active in suppressing the slave trade there. [3] This experience persuaded him to support the cause of abolition, and in 1854, he published a 390 page book, Africa and the American Flag.

He also became a frequent speaker on the Abolitionist circuit. [3] Foote was promoted to Commander in 1856, and took command of the USS Portsmouth in the East India Squadron. With this command, Foote was assigned the mission of observing British operations against Canton, China, during the Second Opium War. This eventually resulted in his being attacked from Chinese shore batteries. [3] Foote led a landing party that seized the barrier forts along the Pearl River in reprisal for the attack.

[6] This led to a short occupation by the U. [3] Civil War and his death When the American Civil War began in 1861, Foote was in command of the New York Navy Yard. On June 29, 1861 Foote was promoted to Captain. From 1861 to 1862, Foote commanded the Mississippi River Squadron with distinction, organizing and leading the gunboat flotilla in many of the early battles of the Western Theater of the American Civil War. Even though Foote was an officer in the United State Navy, the Western Flotilla was under the jurisdiction of the Union Army.

In early February 1862, now holding the rank of Flag Officer (equivalent to the modern Commodore), he cooperated with General Ulysses S. Grant against Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. Despite heavy damage to one of the gunboats, Foote was able to quickly subdue the fort. Several days later Grant and Foote moved against Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. Hoping for a repeat of the success at Fort Henry, General Grant urged Foote to attack the fort's river batteries.

Fort Donelson's guns, however, were better placed than Fort Henry's were. Three of Foote's gunboats were damaged including the flagship, USS St.Foote himself received a wound in his foot. For his service at Forts Henry and Donelson, Foote received the Thanks of Congress.

After repairing his flotilla, Foote joined with General John Pope in a campaign against Island Number Ten on the Mississippi River. In July 1862 Foote received a second Thanks of Congress, this time for the battles of Fort Henry, Fort Donelson and Island Number Ten. [7] Later in 1862, Foote was promoted to rear admiral. [3] In 1863, on his way to take command of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, he suddenly died. His untimely death in New York shocked the nation.[8] He was interred at Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven. [9] Namesakes Three ships were named USS Foote for him. Civil War Fort Foote on the Potomac, [10] now a National Park, was also named for him. The item "CDV Photo Union Civil War Soldier Armed Double Pistols & Knife Elmira NY 1860s" is in sale since Monday, May 09, 2016.

This item is in the category "Collectibles\Militaria\Civil War (1861-65)\Original Period Items\Photographs". The seller is "dalebooks" and is located in Rochester, New York.

This item can be shipped worldwide.- Country/Region of Manufacture: United States